|

| " ... and then the book was banned!" |

Are things looking a little pear-shaped in your neck o' the woods, Dear Reader? Or is it the humdrum of the workaday that cries out for a diversion? Forsooth, you are in luck, for the first of many gems mined from my recent read* leads to today's Small Adventure:

"Any Man that has a Humour is under no restraint or fear of giving it Vent; they have a Proverb among them, which, may be, will shew the Bent and Genius of the People, as well as a longer Discourse: He that will have a May-pole, shall have a May-pole."

So did sayeth one 25-year-old playwright Mr. William Congreve** to Mr. John Dennis in his letter "Concerning Humour in Comedy" in 1695, wherein he goes on rather about the Source of Humour***.

|

Humour went thataway ...

William Congreve

Sir Godfrey Kneller, 1709, NPG 3199

© National Portrait Gallery, London |

But hunting down the May-pole proverb? Purists might suggest this is a topic for a May Day contemplation, but tra la to that idea. And yet, after perusing the letterly banter (also reprinted by J.E. Spingarn later as Critical Essays of the Seventeenth Century, if you have a copy handy), and getting no joy from Mr. Dennis either about the humour intrinsic to Maypoles, & finding only one other unrelated mention across the whole of the interwebs****, I thought elucidation may come by employing traditional Flying With Hands research tools and, in this fashion, simultaneously compensate by enriching our lives with images thusly:

|

Visually punning Christopher Kane AW16 anyone?

She that is a May-pole, shall be a May-pole ...

[And yet I don't remember seeing this look in my 'hood] |

|

How about some frolicking Monopolists?

Puck Magazine obliges with some May-pole satire

Frederick Burr Opper chromolithograph, 1885 |

|

| Or was this what Congreve had in mind? |

Those more familiar than I with Maypoles, Morris Dancing and the stock-in-trade of Merrie Olde England can see I am barking up the wrong tree with this illustrative crop, as the ribbons and cats are all Victorian embellishments. And while England flip-flopped between Catholic and Protestant mores in the 16th and 17th centuries, the Maypole was banned for stretches as idolatrous symbols of resistance. But they were back in fashion by the time of the Restoration, and Maypoles beheld by Congreve & Friends rather more looked like this, viz:

|

Maypole before London's St. Andrew Undershaft,

As imagined before Protestant zealots destroyed the "Pagan Idol" in 1547.

Penny Magazine wood engraving, June 14,1845 |

|

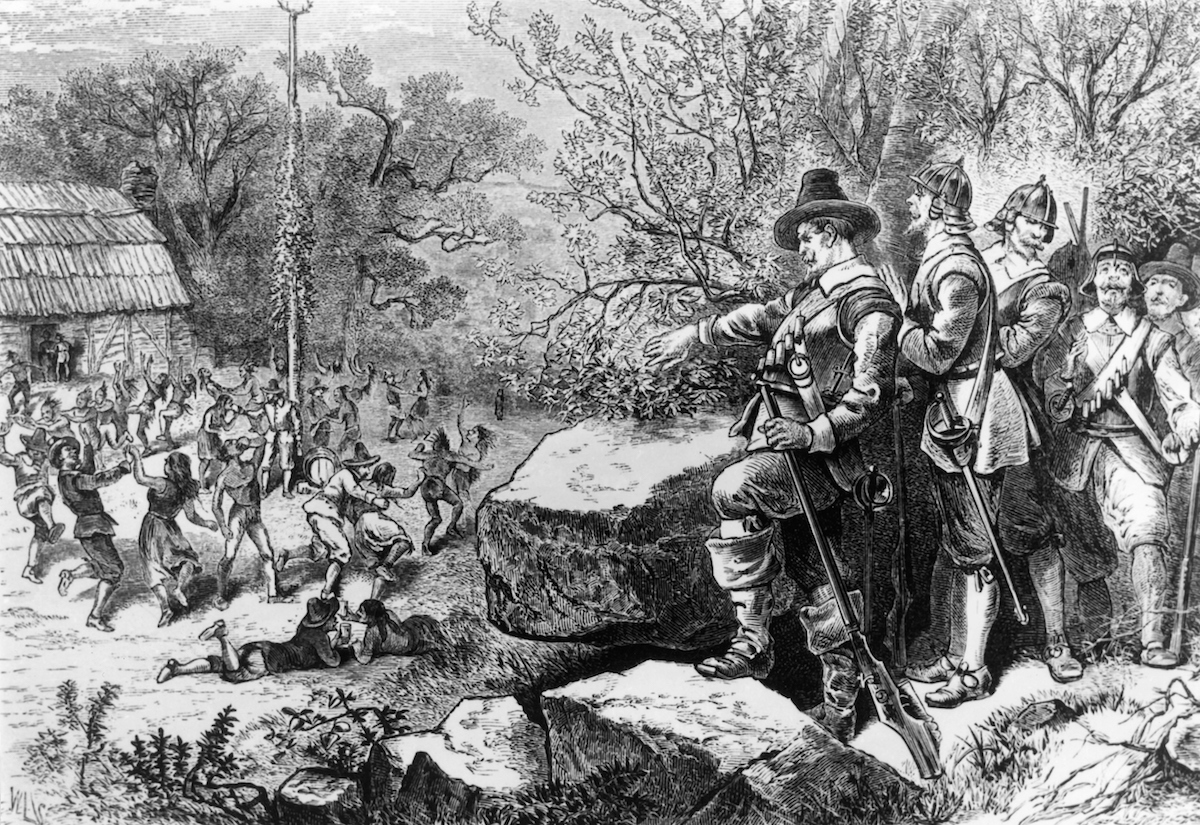

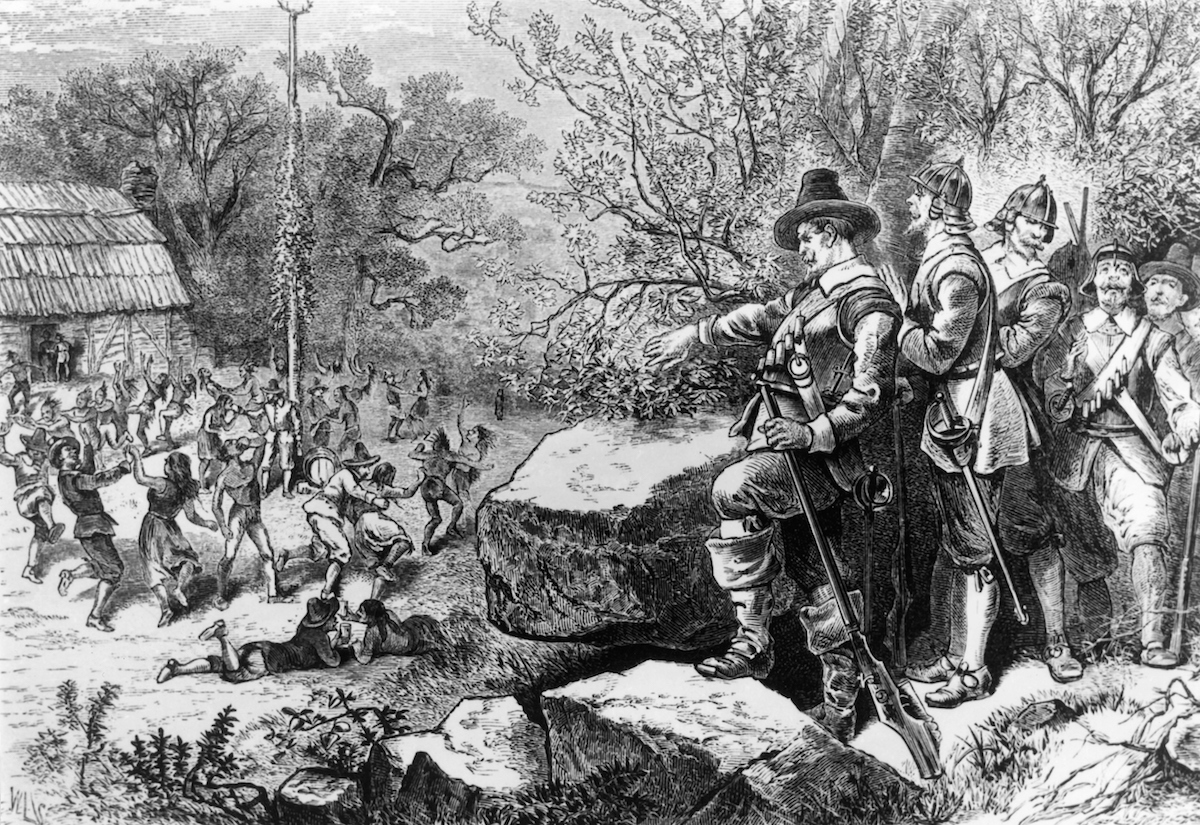

Sprung!

The infamous 80-foot Merrymount Maypole in Massachusetts, 1628

C19th engraving of grumpy Puritan Militia surveying the sordid scene

|

Aha! Now it seems to me that while the Maypole's politically-saucy recent-ish history is the simplest explanation of its allure to the satirist, I prefer an idea that it's this Merrymount Maypole that could be the source of Congreve's proverb. For having, through this pictorial sleuthing, inadvertently discovered the tale of Mr. Thomas Morton, the man of the Small Adventure who erected a mighty Pagan-Maypole in the midst of the Good People of New England, we come to the first book to be banned in America! Behold:

|

| Scandalous reading! |

It seems that around sixty years prior to Mr. Congreve's youthful musings, Mr. Thomas Morton - lawyer, libertine and lampoonist - published The New English Canaan, achieving notoriety on both sides of the Atlantic. Within this too-hot-to-touch wit-laden tome, he both eulogised Massachusetts as the paradisiacal Canaan and denounced and lampooned the New England colonists. And so it was promptly banned.

Copies of the book became as rare as hen's teeth, exacerbated by it also falling foul of English censors since it was printed in Amsterdam, a known hotbed of Puritan publishing. And if nothing could whet the intellectual appetite of the young Wits who held court at Will's Coffee-House in London, it is the tale of a fellow-lampoonist being censored. And a Merrie Maypole being at the heart of the matter*****.

|

The Wits at Will's

Pope's Introduction to Dryden at Will's Coffee-House [inc. Congreve clubbing around]

Eyre Crowe, 1858 |

Well, that's My Theory, anyway. I've not found a shred of evidence to suggest that fifty years after Morton's decease, Congreve and his literary cronies had ever read or even got their mitts on a copy of The New English Canaan or were still talking about it, but I rather believe just mentioning the word Maypole would bring a glint of mischief into their all-knowing eye.

* A treasure-trove known as Before the Romantics: An Anthology of the Enlightenment chosen by Geoffrey Grigson, 1946, and which will provide seemingly endless fodder for Flying With Hands! Chockfull of Pope, Johnson, Diaper, Swift, Dryden &c. &c. for the oh so interested.

** My book's small excerpt, wherein his observation that "there is more of Humour in English Comick writers than in any others" can also be "ascribed to their feeding so much on Flesh, and the Grossness of their Diet in general", is footnoted with the infamous encounter between Voltaire and Congreve, where V may have been insolent, C may have been a literary snob, and V may have later retracted his critical comments in a mea culpa.

*** To wit, upon heading to the fountainhead, Letters upon Several Occasions: Written by and between Mr. Dryden, Mr. Wycherly, Mr. -, Mr. Congreve and Mr. Dennis, 1696. he exposits upon why "Humour is neither Wit, nor Folly, nor Personal defect; nor Affectation, nor Habit; and yet, that each, and all of these, have been both writte [sic] and received as Humour", & offers up his understanding of Humour to be "A singular and unavoidable manner of doing, or saying any thing, Peculiar and Natural to one Man only; by which his Speech and Actions are distinguish'd from those of other Men" and throws in some Choller and Flegm and Spleen. In other words, he helps no-one who is trying to understand what a GSOH means in the Personal Columns.

**** An archived 1964 US Choristers Guild newsletter equals a total dead-end in my book!

***** In a nutshell, the shady-all-round Devonshire-born Morton had been living in a Utopian colony in Massachusetts, with the non-PC-name "Merrymount" (as in non-Puritanically-Correct), established by him and a notorious pirate soon after the Mayflower landed. His Small Adventure runs the gamut of "subversive" living in the eyes of his dour Puritan neighbours, viz. pagan practises and "going native" with the local Algonquin tribe and Bacchanalian May Day performances, but his worse crime was to cut in on the settlers' fur trade and arm the said Algonquins. An eighty-foot antler-topped Maypole erected at Merrymount two years in a row was the final straw. The Plymouth Militia arrested Morton, the Maypole was cut down, he narrowly avoided execution and was banished back to Olde England via a spell on a deserted nearby island, and Merrymount was sacked. Spells in prison ensued, but, ever the lawyer, Morton bounced back and tried to sue the Puritans through the Massachusetts Bay Company. King Charles I, naturally hostile to the Puritans, ultimately revoked the Company's charter, and Morton published the fruits of his legal campaign as his book, The New England Canaan.

Image credits: 1, 5: via Pinterest; 2: National Portrait Gallery, London; 3: Rex via MarieClaire.co.uk; 4: Wikimedia Commons; 6: The British Museum; 7: Penny Magazine via Google Books; 8: via Project Gutenberg; 9: via ArtRenewal.org